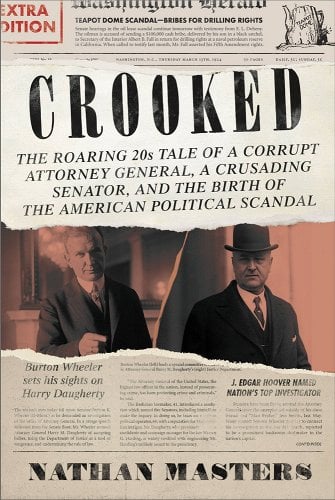

Impressions

Whenever I watch a political thriller on Netflix I think, "No way, none of this stuff actually happens." Crooked proved me wrong. This is a remarkable narrative non-fiction book about politics, Senate investigations, and bribery charges (I promise Nathan Masters makes all of that interesting) that goes all the way up to the top of the executive branch.

This book is about power, money, and the realization that any political office is just held by an ordinary person tempted by both of those things. It also sets the stage for one of the 20th Century's most notorious lawmen: J. Edgar Hoover and the birth of his shoe-shined black-suit slick-hair FBI. Reading this book helped shed some light on why Hoover was so ruthless in his documentation and the discipline special agents had to follow. Maybe he realized that without those things, a “secret police force” would do the deeds of the highest bidder.

Notes

- I know a book will be good when it has a page titled “A Note to Readers” with this warning:

This is a work of nonfiction, with no invented details or dialogue. Anything between quotation marks comes directly from historical sources, including FBI case files, Department of Justice records, newspaper reports, memoirs, archival collections, and the 3,338-page transcript of the Hearing Before the Select Committee on Investigation of the Attorney General.

- “When public officials were in the pocket of powerful interests, the odds would always be stacked against the little guy.”

- “Where else but a courtroom would a soot-stained miner and the mighty Anaconda Company be treated as equals?”

- The FBI first started as, essentially, a secret police force: the Bureau of Investigation. It was created in 1908 by executive action and was acting as the Justice Department’s in-house detective agency. It was not authorized by Congress.

- William Burns was the head of the Bureau Investigation and John Edgar Hoover was his young deputy.

- President Harding was a master at delivering “sonorous and empty remarks. It was his trademark. He even had a name for it–bloviating.”

- Calvin Coolidge was nicknamed “Silent Cal.” “Coolidge hated small talk and, although he tolerated social events, favored his own company to that of others. He slept nine hours every night, napped two hours in the afternoon, and in his waking hours went long stretches of time without opening his mouth, even during official functions.” He was “the sly and laconic Yankee rustic, who was cleverer than he appeared,” wrote one observer.

- Harry Daugherty hitched his train to President Harding throughout his whole career. This proved favorable when Harding was elected president, but disastrous after he died. Sure, he’d spent his life helping Harding navigate the ins and outs of political circumstances but, other than that, he hadn’t really done anything. After Harding died, his time as a free rider was coming to an end. That’s the danger of hitching your life and career to the success of someone else’s train.

- Just because someone votes to do something, or says they will do something, doesn’t mean they actually will. Robert M. La Follette understood this when, after presenting enough evidence to get a unanimous Senate vote to authorize an inquiry by the Committee on Public Land and Surveys, no one actually did anything. After seven months, the committee hadn’t even had their first meeting yet. The Senators vote was more for show. If something ever did turn up that was evidence of foul play, they wanted to be able to look back on the vote and say, “Look, we voted for that to pass,” but that doesn’t mean they were incentivized, or willing, to actually do any real work. (51)

- After Senator Burton Wheeler made his first address to the floor, though it was unprecedented he did so being a junior Senator, some people helped out. Sen. William Borah of Idaho said, “Wheeler, there’s a chance for you to make a reputation for yourself…If you’re honest, and you’ve got ordinary intelligence and you’re willing to work.” “How do you figure that,” Wheeler replied. “So damn few want to work.”The bar for doing something great in life isn’t as high as you think. With some hard work and honest intelligence, you can go quite far.

- Wheeler was willing to go outside of the Senate norms to do things no junior senator had done before (crossing party lines) and found out he could do things better that way. Maybe that’s the lesson with bureaucracies, sure there are rules and stupid regulations people have to follow, but if you’re willing to work outside of those norms, respectively of course, you might actually get stuff done.

- “Public trust ultimately came down to nothing more than the private integrity of individuals…A Justice Department true to its name hinged on the honesty of one man.”No matter how powerful the position someone may have, it's held by a human being. One who is tempted by power, love, money, and success just as much as anyone else is.

- The Bureau of Investigation was initially created to be just an in-house detective agency for the Justice Department, created under Roosevelt. But when America entered the First World War, the Bureau, at the orders of President Wilson, doubled its detective force and increased its budget to nearly $2 million. Its new job entailed protecting the nation against enemies – foreign and domestic. By 1920, it had 579 sworn field agents assigned to headquarters all across the nation. By that time, it was a full-fledged domestic intelligence agency, doing just about all they can to gain access to and information about anyone who had left-leaning political philosophies.

- When you embark on a mission, be crystal clear about what your goal is. For Burton Wheeler, he didn’t want to convict Daughtery in a Court of Law, that would entail a whole other host of problems and resources, he just wanted him out as Attorney General because he was abusing his post. So, all Wheeler had to do was dig up and present evidence in a way that the court of public opinion would resonate with, so they would put enough pressure on Coolidge to get rid of this bad man. Knowing that was the goal, it made it easy for Wheeler to sort through evidence and know what to present, and how, to tell the best story.In the epilogue, the author writes, “Wheeler’s particular genius–which seems almost counterintuitive today–was to seek justice instead in the court of public opinion. There, unbound by the rules of the criminal justice system, his freewheeling investigation forced Daugherty’s retirement from public life and consigned America’s most corrupt attorney general to the judgement of history. For all his successes, Burton Wheeler couldn’t guarantee another Harry Daugherty or William J. Burns would never undermine justice again. But he did show that it was a fight worth undertaking.

- Harry Daugherty had been able to get away so long with his swindling because he had Jess Smith do all of the dirty work. “In matters of official business, Harry Daugherty met with no one but Jess Smith, who then worked out the details with other parties. Two-way meetings were the rule. Three-person conferences were forbidden: too many witnesses.”

- After Coolidge replaced Daugherty as Attorney General, Felix Frankfurter, a Harvard Law professor, cofounder of the American Civil Liberties Union, and former Justice Department lawyer, told Stone, “The key to [your] problem is, of course, men. Everything is subordinate to personnel, for personnel determines the governing atmosphere and understanding from which all questions of administrative organization take shape.”Stone appointed J. Edgar Hoover to the head of the Bureau of Investigation, and Hoover accepted on certain conditions: He said, that “The Bureau must be divorced from politics and not be a catch-all for political hacks. Appointments must be based on merit. Second, promotions will be made on proved ability and the Bureau will be responsible only to the Attorney General.”Stone: “I wouldn’t give it to you under any other conditions.”

- “Over these next few months, which would be so critical for the transforming the troubled agency into ‘the greatest detective force in the world,’ as [Hoover] described his goal to the press, the attorney general would personally supervise its major investigations, approve all hiring decisions, and, most importantly, steer the Bureau through a series of major policy changes.”Doing something great requires actions that don’t scale.