Every good story-at-sea has at least two of three elements: a shipwreck, murder, or mutiny. While this tale definitely had the second, the third is questionable, and the first doesn’t appear at all.

Richard Snow does his best to recount the complicated and mysterious story aboard the Somers, which is magnificent.

In 1848, the Somers, a US brig-of-war, set out from New York Harbor on a journey south with young naval officers. Its mission was to deliver papers, but its real mission was to teach its young crew what sea-faring life was like. (The Naval Academy at Annapolis was yet to exist, and, as a result of what happened on this ship, would be created.)

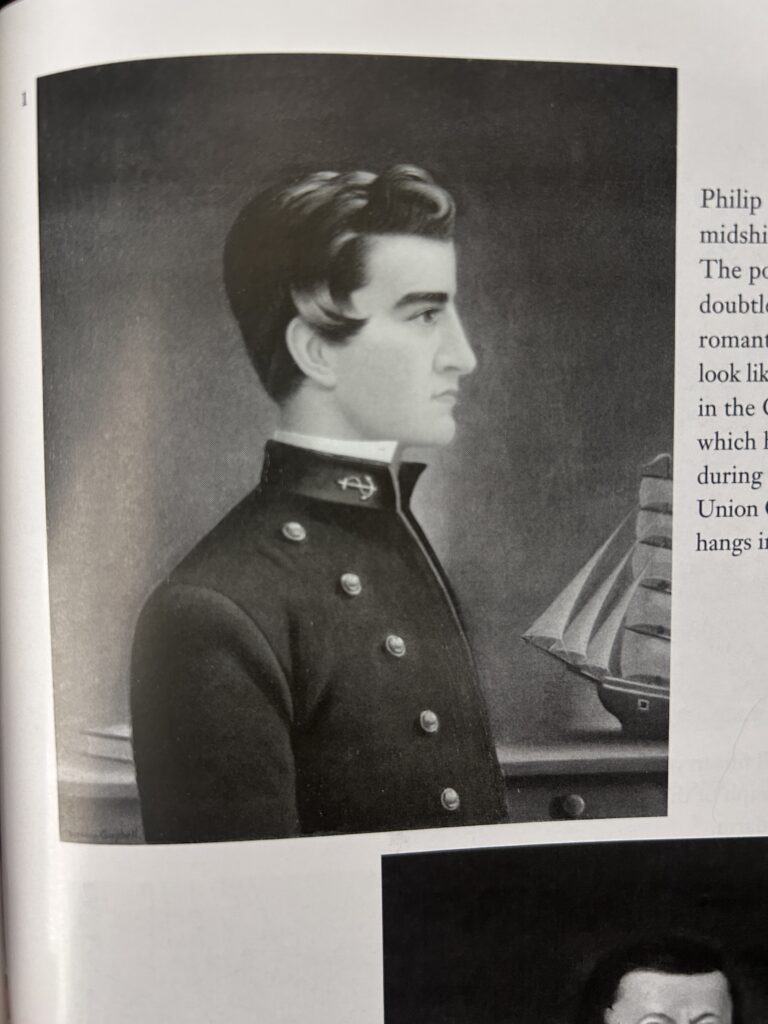

Phillip Spencer

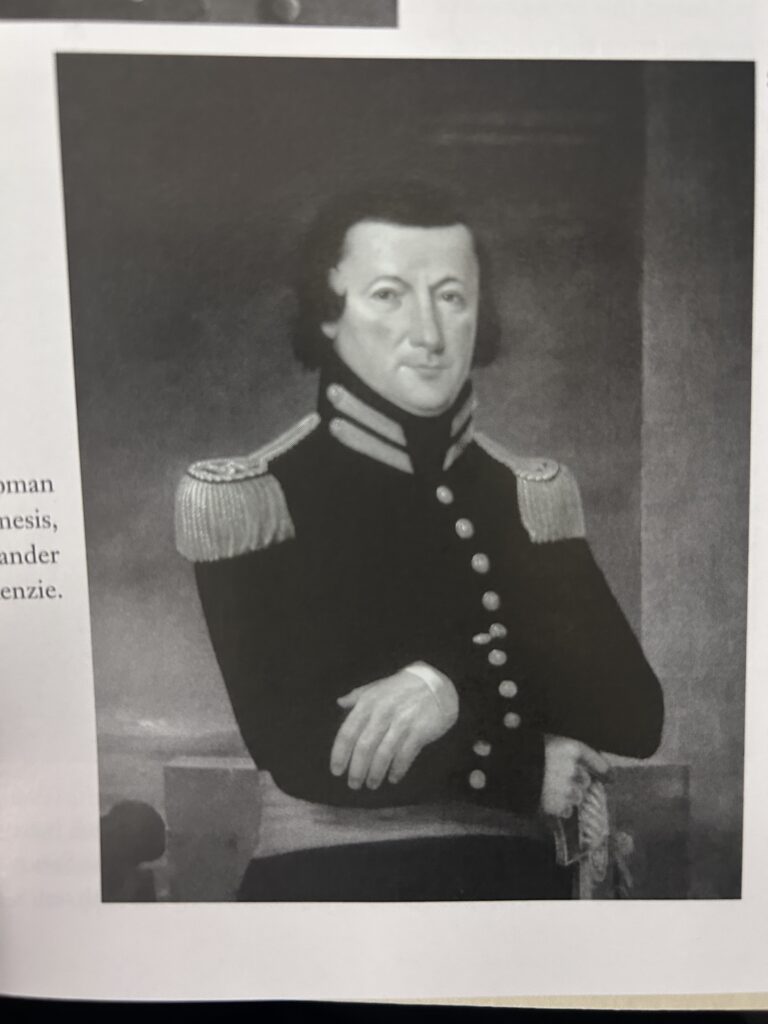

Aboard the ship was Phillip Spencer, a “young punk” who just so happened to be the son of the Secretary of War for President John Tyler. Events ensued aboard the ship—a supposed mutiny led by Spencer—which caused Captain Alexander Mackenzie to hang Philip Spencer and two of his comrades.

The book’s first half explains the background of some of the crew and the events that lead to the eventual hanging. The second half covers the dramatic “inquiry” and court-martial into Captain Mackenzie’s behavior that sought to determine: 1. Was a mutiny really going to happen? And 2. If so, was hanging the culprits necessary?

The drama rests in the fact that while Mackenzie claims a mutiny was coming, and Spencer admitted to talking about it, the actual likelihood of a mutiny happening was not great. So, the question was, did Mackenzie act too rashly? Some thought he did, others thought he acted valiantly. Maybe the fact that this was the only mutiny in US naval history gives us the answer.

At both the “inquiry”—a formal investigation simply to gather facts—and the subsequent court-martial, the captain’s behavior was deemed appropriate, and he faced no punishment. Philip Spencer’s father and the bride of another hanged were calling for Mackenzie’s prosecution for murder. They doubted a mutiny was really going to happen and thought Mackenzie’s punishment was overboard (no pun intended). Mackenzie’s log of whippings on board reveals he might be quick to punish. In total, he administered over 2,000 lashes to sailors who acted out of line, the youngest of which was a mere boy.

Captain Alexander Mackenzie

And that’s the story. Dramatic and entertaining? Yes.

My one critique (which, as a professional, I am not) about the book was that the author relied too heavily on direct quotes. In a story like this, having primary sources is important, but at times, the frequent direct quotes stopped the flow of the story.

For example:

On March 28, “the court met this day in pursuance of adjournment…And the court being cleared, the court proceeded to consider the charges and specifications, and to make their finding thereon.”

Why not just write, “On March 28, the court met to consider the arguments and determine a verdict.” I understand the appeal of quoting the direct source, but the quote is just cumbersome.

I also didn’t like how he referenced two modern-day inventions as an

Still, like with any part of history, there is much to learn. Mainly, one is left asking why Mackenzie risked his career to hang the Secretary of War’s son on mere talk of mutiny and a picture of a ship with a black flag. Such is the lesson to take away from this. It’s hard to undo hanging someone, yet it seemed as if Captain Mackenzie was set on this method of discipline from the very beginning. Why?

It’s theorized in the book’s epilogue that his decision was intentional. In a time of peace, it would be hard for a ship captain to become famous, as many of his peers did in the Battle of 1812.

So, was the decision to hang the son of such a prominent figure Mckenzie’s way of being remembered? Perhaps. Here we are, two hundred years later, still talking about him.